News

News

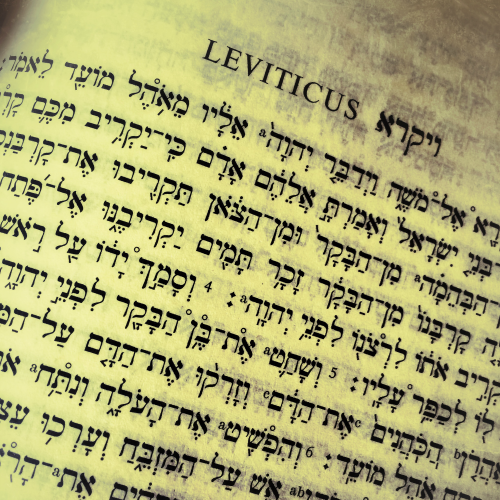

The Holiness Code: Torah Reflections from Central Members

September 25, 2018 | Worship and High Holidays

On Yom Kippur afternoon we read a section of the Torah known as the holiness code. This section, found in chapter 19 of Leviticus, is at the heart of the Torah and contains some of the most moving commandments within our tradition. We asked six of our members to reflect upon one of these commandments. They did so in front of our community just after we chanted from the Torah. We are grateful for their personal and moving insights which are shared below:

Alice M. Greenwald

Leviticus 19:1 and 19:2

“The Eternal One spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the whole community of Israel, and say to them: You shall be holy, for I, your Eternal God, am holy.”

What does it mean to be holy?

The roots of the Hebrew word for holy, Kadosh, and the Latin word “sacred” both derive from the idea of separateness… as when we distinguish Shabbat from the rest of the week, separating holy from profane.

The Days of Awe too mark a separated space, distinguished from the rest of the year.

Yet the Holiness Code we read on this holiest of days is all about the rest of the year and how we should relate to each other in our daily lives; how we should, in fact, connect with one another.

Which got me thinking about when I have felt holiness:

Like the time I touched my father’s arm as we talked one night, shortly before I left for grad school. I had a premonition he would not be here forever. It’s hard to describe but I felt a kind of fire inside him, a unique energy, the love that connected us.

He would die of a heart attack days later. It’s been 45 years, and I still feel that fire.

Or – a very different moment – when I went whale watching off of Baja California. A female grey began to swim alongside us, showing off her calf. I looked into one enormous eye, and in that instant—mother to mother—I felt a depth of spiritual connection and exquisite mystery I am unable to convey.

And, the holiest moment? Hearing my grandson Ezra say “Nanny” for the first time – and experiencing an electric shock of pleasure and grace, wholeness and fulfillment; a profound awareness of connection.

Holiness seems to be about connecting: to something more than ourselves; to each other; to something eternal.

This holiest of days asks us to connect not only to the essence of who we are as individuals but to mitzvot that command us to care for one other.

The commandment to be holy is directed to “the whole community…”, with the Holiness Code providing a case study in how to conduct our lives with empathy: in business and with neighbors; within families and with strangers; with those less able or fortunate.

The commandment does not say “you are holy.” It says, “you shall be holy.” Holiness is a process of becoming.

Yet, we can only become a holy community if we connect with empathy.

When we strive to fulfill the commandments of the Holiness Code… when we live our lives with concern for others in our hearts… when we pay attention to those rare moments of deepest connection… only then, do we come closer to fulfilling this very first commandment—to be holy—the one for which all the other commandments are required.

Cori Berger

Leviticus 19:3

“Revere your mother and your father, each one of you.”

Back in July, when I was considering accepting this honor of sharing a Torah interpretation, I quickly calculated that this Yom Kippur, this Yizkor service, would mark the 10th anniversary of my dad, Ira’s passing. Knowing that taking part in the service would be a meaningful way to honor my father’s memory, I accepted.

So you will understand my goose bumps when, seven weeks later, coincidentally on my birthday, I learned that the text I was assigned to reflect upon is the first verse of the holiness code, commanding us to “Revere your mother and father”.

As Jews we are commanded again and again to obey and to honor our parents. We have a responsibility to show our parents reverence and respect, to follow their rules and to care for them as they age. These obligations are fairly straight-forward and fulfill the commandment of bringing honor by showing respect.

Parents also have responsibilities. The V’ahavta prayer - taken straight from the Torah - commands parents to instill values in their children. By modeling good behaviors and positive character traits, a parent teaches their child how to live in a way that would, in turn, bring honor back unto the parent. If a parent does their job well and gives their offspring the tools and skills to find purpose and happiness, then the child will go on to live a life of integrity and meaning – and that I believe is one of the greatest ways a child can honor a parent.

My dad taught me countless life skills, everything from how to ride a bike, to how to be patient and tolerant. And while he wasn’t a particularly observant man, he made it clear that his Jewish heritage was important to him.

I remember, just after he passed, while clearing out his desk, I found a well-worn pamphlet containing the Mourners’ Kaddish prayer in his top drawer. His mother had passed away a year before and in that moment, I realized that he had sat at his desk for the last year saying Kaddish for his mom. He never spoke about it, but honoring my grandmother would have been important to him. The pamphlet now resides in my home. It is the one I used to say Kaddish for my dad at my dining room window for the eleven months after he died.

And now 10 years later, how do I continue to honor my father? I observe his Yahrzeit and say I Kaddish – these obligations are clearly spelled out for us. But the moments that I feel closest to my dad are when I do things like this. Sharing teachings from the Torah before my community at the High Holidays is an honor that is meaningful to me. Knowing that my dad would share my pride today, allows me to continue to honor him.

Bob Horne

Leviticus 19:12

“You shall not hate your brother or sister in your heart. Rather, you must reason with your kin, so that you do not incur guilt on their account.”

I was immediately struck by the low bar set by this commandment. Don’t hate?! Why not command us to love our siblings? Or even just to like them?

This commandment reminded me of the many fights I had as a child with my younger brother, David. It would generally go like this …… I would say something to push his button, he would hit me, I would beat him up, and then I would tell my parents that he hit me first. There were some – ok, many – stressful times, but we never got to the point where we hated each other. As we grew into adulthood, we argued less, stopped the hitting and have enjoyed many good times together. Today I am very close with David, and we do in fact have a loving brotherly relationship.

Sadly, however, I have seen with my mother and her sister what can happen when a disagreement between siblings degenerates too far. They were extremely close growing up, but over the past 15 years one sibling has been hurt so much by the words of the other that she no longer wants to communicate with her sister – and rarely does so. I am afraid that the likelihood of their reconciling is low. It has been an extremely difficult situation for me to witness, and I can only imagine what it has been like for my mom and aunt.

I know that they are not the first siblings to have had a serious falling out, but what is happening between them is the “disaster scenario” that the Torah is trying to prevent.

I commit to work hard to ensure that this scenario never occurs between me and any of my family members. But this commitment is a low bar, as my daughter, Sarah, pointed out to me last night. Therefore, I also commit to doing my best to foster a loving relationship with each of my family members by engaging empathetically and constructively with them.

Jonine Bernstein

Leviticus 19:18

“Thou shalt not avenge, nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people, but thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself”

I hold a photo image in my mind from 1983. I was spending the summer with my parents in the French countryside. The house we were staying in was nestled into the hillside a hundred stone steps above a curvy narrow, single lane road.

We were leaving for our daily adventure, beginning with our daily headache –backing our car out of our tiny garage, in the middle of a blind curve. Dad drove while mom stood across the road directing him.

I was at the top of the steps when I heard brakes screeching.

My mother lay crumpled in the street where a speeding car had hit her. (Spoiler alert- mom’s fine, she’s sitting right here in the congregation).

Dad scrambled out of the car, and left it in the middle of the road. Limping from an old war wound, he lumbered to mom, and dropped to his knees. She was in pain, but mostly, she was terrified. Gently covering her 5’2” frame with his 6’4” frame, dad curled himself around her, literally wrapping her in his protection. And that’s the photo image I carry.

That image of my parents lying in the road affected others as well. One ran to call an ambulance. Another sprang forward to offer medical help. A third, moved dad’s car to clear the road.

As I reflect on “love thy neighbor”, that photo image returns. The people close enough to see my parents, all rushed to offer help. However, the people around the curve, who couldn’t see my parents reacted differently, without understanding. Horns blared. Voices shouted.

To me, love thy neighbor means see thy neighbor, and see thy neighbor means cultivating empathy and understanding.

That’s what that photo image is about for me, as well as the love between my parents.

Today, I pledge, that when I feel frustrated by my neighbor, I’ll strive to see them clearly, and to understand—even, when they’re strangers, in a foreign country, who are blocking my road.

Lisa Piazza

Leviticus 19:32

“You shall rise in the presence of the aged and show respect for the old, you shall revere your God; I am the Eternal One.”

Food was plentiful in my childhood home. My Italian father sold produce. My Polish mother mastered the cuisine of her husband’s family. Meals were always fresh and homemade, on schedule, and attendance was mandatory. Food—an expression of love—nourished wisdom.

Formal education, in contrast, was limited. Our only teacher, my mother’s elder sister, Sister Clemens, passed away when I was 11. And, my father and big brother developed neurodegenerative illnesses soon thereafter, robbing them and me of their vitality.

Sometimes, a mensch is needed.

God called upon you to nourish the poor and the stranger, and you answered, “Hineni, Here I am.”

When I was a teen I fenced at the NY Fencers Club, the place for foil fencing. It was also my first social encounter with professional people. There, I met Bob Bases, a radiobiology researcher. He was quite a spirit, always positive, energetic, and supportive.

I was approaching a gap year before med school. “Bob, do you need any help in your lab?” I’m not sure he did. Bob smiled broadly and said, “Well, in fact I do!” I worked in his lab that year, and twice a week after work we drove from Einstein to New Rochelle. There Judy, his wife, a master chef and caterer gave us a bite to eat before we’d head to the club.

When I took time off from medical school to pursue my fencing, I again worked for Bob, and for Judy on the weekends. They invited me to dinners with their doctor friends. And, after I had surgery, Judy cared for me and stocked my fridge with food.

Some years later, when I was an intern working too many hours a week, I still made it to the fencer’s club, my accessory family. “Bob, do you know any nice guys?” And Bob introduced me to David Golub, who became my husband.

Looking back upon my life, I am thankful for this nurturing, during a time when the weight of illness in my family was overwhelming.

To Bob and Judy Bases, two elders in my spiritual Kibbutz, you gave me inspiration, a job in your lab and in your kitchen, real support in times of need, professional society and mentorship and my family.

I stand today in your presence and honor you.

Yaakov Shechter

Leviticus 19:33 and 19:34

Who were the gerim – the strangers? While we don’t know many details, they were clearly a minority among the Israelites. Why is it so important to treat them as equal, even love them? Atem yedaatem et nefesh hager. Because you were strangers in Egypt. The emphasis is on nefesh, the soul, the psyche.

The gerim commandment undoubtedly inspired the authors of Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948. Israel was established as a democratic state with full citizenship for our present-day “strangers”/gerim, the 20% Arab minority, and with Arabic as a second official language.

My personal encounter with a “stranger” happened when I was a 19-year old soldier in the Israel Defense Forces’ elite Nachal Brigade. We were sent a new recruit, an Arab Kurd, and I was assigned to be his mentor. He was older than us, looked different from us, and spoke poor Hebrew. I resented the assignment but carried it on reluctantly, often making fun of his name, Chababa, his accent, his culture. We made cruel jokes about him, even to his face. He tolerated our taunts, trained very hard, so eager to become an IDF soldier. Eventually he gained our respect. After eight months he was transferred to another unit, and I lost touch with him. From time to time I would think of him, and feel ashamed of my cruel, arrogant behavior.

In 1975 I surprisingly received a picture postcard from Chababa. It showed an older, dignified Chababa, with an elegant wife, and two tall teenage sons. The photo was taken in honor of Chababa’s 20 years of service to the Negev Water Treatment Center. At the bottom he wrote: “To Yaki Shechter, my best teacher ever. I couldn’t have done it without you.”

I never saw Chababa again.

He died in June of 2014.

I am still seeking his forgiveness.

Al chet shechataanu lefanecha b’latzon: For the sin of making fun of strangers.

Al chet shechataanu lefanecha be’einayim ramot: For the sin of arrogance.

Forgive me, pardon me, grant me atonement.

News by category

Contact

Please direct all press inquiries to Central’s Communications Department via email at .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address), or phone at (212) 838-5122 x2031.